Freight Market Outlook

2022-2024

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shipping market has been uncertain at best, and extremely volatile and disruptive at worst. The pandemic heavily impacted the capacity of the workforce across terminals and airports, ultimately causing delays across the supply chain and skyrocketing freight rates.

To help you navigate the crisis throughout 2022, we’ve put together key data and information based on our industry experience, and research and have forecasted what the world of global shipping will look like over the next few years.

Please reach out to the team at International Cargo Express if you need further assistance. We hope you enjoy the read.

When the pandemic forced governments across the world to introduce lockdowns, demand for international goods came to a grinding halt. In a reactionary move, shipping carriers cancelled voyages (blank sailings) and many placed their vessels out of service.

However, 2020 was a year of two halves: the first was dominated by a severe trade contraction where carriers blanked record sailings (reaching as high as 30% of sailings on some trades); and the second half included a recovery in cargo demand on an unprecedented scale.

With reduced services on the market, the world’s carriers were unprepared when demand significantly spiked. Further challenges also arose when voyages were interrupted because of staff testing positive for COVID-19.

2020: The Start

How Did We get here?

Pandemic

Outbreak

Increased

demand

Sick

workers

Port

disruptions

Blank

Sailings

Many of the largest overseas ports were operating efficiently prior to COVID-19.

Outbreaks of COVID-19 occurring either at ports or on vessels caused further disruptions to shipping schedules, closures of terminals and reduced productivity. Quarantine measures that were implemented resulted in reduced staff numbers.

On top of that, scheduling was affected by various restrictions at ports. Mandatory quarantine periods for vessels entering ports and restrictions on crew disembarkation around the world created additional uncertainty for shipping lines, as well as contributed to scheduling disruptions and staffing issues (for example, rotation of crew members).

The closure of the Yantian terminal in mid-2021 contributed to a massive backlog of containers for export and a diversion of vessels to alternative ports in the region. The result was a further deterioration in port congestion globally, and a sharp rise in freight rates across the board.

Port Operations become fragile

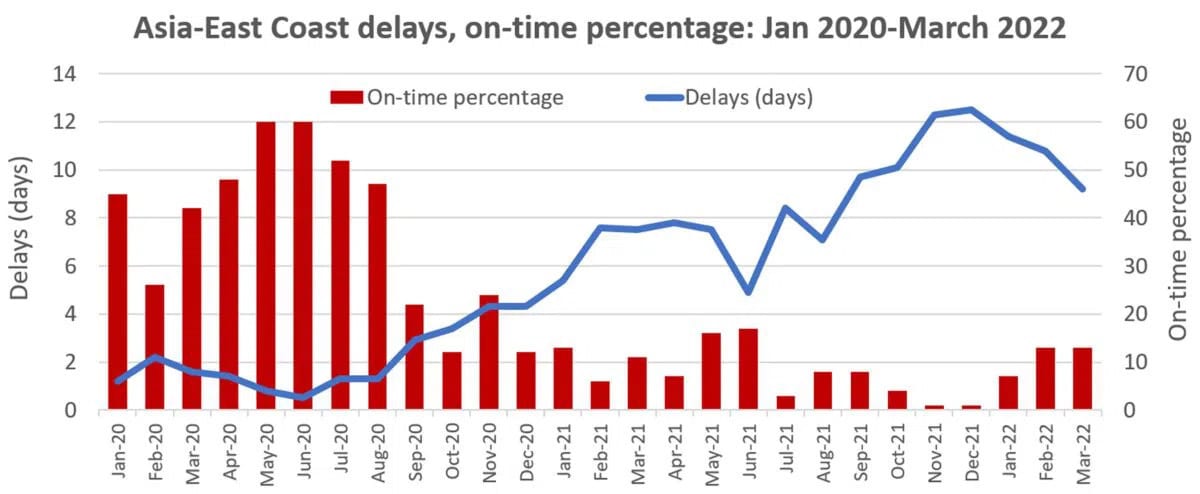

Schedule reliability dropped to 33.6% in August 2021, the lowest in 10 years.

Increased turnaround times at ports resulted in delays. Vessel delays led to shipping capacity shortages.

For example, if a shipping line offered a service that had previously taken 6 weeks to ship a set number of containers, this was often extended to 7 weeks or more. This resulted in an overall loss of capacity in the market.

As a response, shipping lines ended up omitting ports on their route in an attempt to get back on schedule.

Congestion at overseas terminals and delayed vessels resulted in over 20% of ships bypassing Port Adelaide, for example. The increase in idle time at Port Botany was especially noticeable, increasing from 11.9 hours to 21.2 hours; shipping lines often chose to skip the port entirely.

To avoid delays, shipping lines also tried to adopt a strategy of delaying advertised sailings (‘sliding’). Even though shipping lines have attempted to provide as much capacity as possible, there was a rise in rolled cargo, with one shipping line’s rollover ratio increasing to 35% in October 2020.

All roads lead to...

Port Congestion

As scheduling reliability deteriorated, port terminal operations suffered. The effects of off-window arrivals included vessel bunching, which placed a strain on stevedores’ equipment and labour resources, and led to further congestion.

disrupted shipping schedules

Empty Containers / Equipment

The sharp fall in world trade in the early months of the pandemic disrupted the routine flow of containers – and we haven’t really recovered since.

As an import nation, Australia has a largely imbalanced container trade, with more full containers entering the country than empty containers leaving.

Couple this with the rise in port congestion caused by the sudden increase in demand, industrial actions and blank sailings, and the ultimate result was that not enough empty containers were being repositioned back to critical origin ports.

There is an abundance of exports coming out of China, leading to empty containers piling up in Australia's container yards. With shipping lines unable to dedicate sufficient capacity for evacuation, container yards have become full.

Due to this congestion at container yards, empty containers must be redirected elsewhere, at the importer's cost.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, shipping lines used ‘sweeper vessels’ to evacuate empty containers, clearing local congestion and returning equipment to centres of demand. However, because of the global shortage of shipping capacity and lack of available berthing windows, shipping lines have allocated fewer vessels for sweeping operations. Whilst there is no shortage of containers in the system, containers are stuck in the ‘wrong’ parts of the world.

Truck Drivers

The United States has a shortage of around 80,000 truck drivers (American Trucking Association), which is problematic since 72% of the country’s freight transport moves by truck. Similar shortages are being experienced across Europe, China and Australia. The change in trade patterns and lack of truck drivers has caused many containers to be left inland in various locations leading to unavailability when needed.

Global ports lost over 1/3 of their expected capacity

to ship containers during 2021.

Space on vessels

Shipping lines are allocating capacity to higher value routes and volumes. They are reluctant to carry export laden cargo that is of a low margin and requires investment in equipment (such as food-grade containers), or which needs to be moved to a port where there is lower demand for empty containers. All this has further limited shipping capacity available to Australian cargo owners.

Due to cargo rollover (as a consequence of port congestion and delayed schedules), a greater proportion of space on vessels is allocated to volume that is already contracted. As booked cargo is rolled over to a later service, this leaves less space available for uncontracted cargo, contributing to the squeeze of shipping line capacity.

Lastly, exporters in China have been paying large premiums for empty containers as demand is so high. This further reduces the space available to Australian exports and, therefore, exporters are effectively competing with empty containers to secure shipping slots.

The number of services to Australia declined during the pandemic, despite the increase in demand.

ABUNDANCE OF SHORTAGE

Approximately 80% of Australia’s international air cargo volume is usually carried in the belly of passenger aircraft. Travel restrictions due to the pandemic resulted in a major reduction in passenger flights that would otherwise have moved this cargo.

Air cargo capacity is estimated to have fallen by 91% since the start of the pandemic, driving up the cost of airfreight.

The initial impact of the fall in airfreight capacity caused a shift to increased sea transportation, compounding the already constrained sea freight capacity.

- Freight rates remain at a high level

- Fuel surcharges have become extremely volatile and continue to increase

- Space and service options remain limited

- When cargo arrives, Container Terminal Operators (CTOs) who make cargo available for collection have generally been slower

- Trucks are also generally waiting longer at CTOs to collect cargo

As of April 2022:

air freight isn't any better

The unpredictable development of the pandemic led to congested ports, vessels bunching offshore, and delays in schedules which led to an increase in expenses for carriers.

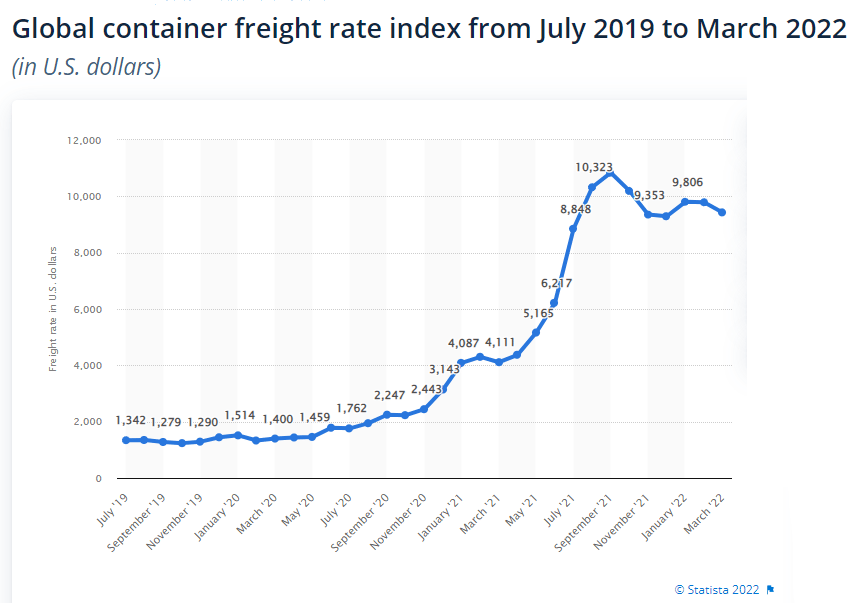

Shipping prices are around 4 or 5 times higher than usual compared to the high season in previous years. Container freight rates on the key global trade routes have increased from US$1,000 in May 2020 to around US$7,500 in September 2021.

Supply Chain pressures from COVID lockdowns in China, the Russia-Ukraine war and rising oil prices, might hinder expectations of a supply chain recovery.

Spot rates for container cargo has fallen since the beginning of 2022. But falling freight rates are seasonal, not structural.

finally,

the freight rates

Low supply

+

high demand

=

price hikes

Shipping lines claim that ship-chartering costs have increased by 773% since late May 2020 and marine fuel costs have near tripled since early 2020.

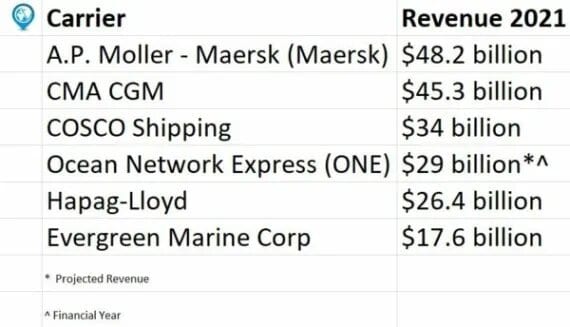

Maersk alone enjoyed its most profitable quarter in its entire 117-year history – a figure of $5.9 billion in Q3 2021. Revenue increased by 55% to $61.8 billion in 2021, up from $39.7 billion in 2020.

Ultimately, freight rates have surged across all shipping lines and cargo owners have few options. It comes down to importers and exporters attempting to outbid each other to secure capacity.

Record Profits for

shipping lines...

Source: Port Technology International

$

0

billion

Is the estimated profit for container shipping pre-tax for 2021 and 2022, according to the latest revised estimate by Drewry.

market overview: china, USA, Europe & Australia

- China’s manufacturing sector has seen unprecedented growth over the past two years. This is expected to slow significantly as of Q1-Q2 2023, as consumers change their spending habits, (looking more toward tourism and services, rather than manufactured items), and lockdowns ripple through the economy.

- As of April 2022, China is experiencing its worst COVID-19 outbreak since the start of the pandemic. Operations in Shanghai port, the largest in the world, are still running, but they are limited. Some of the staff are in quarantine, and some work in a closed-loop system, meaning they practically live at the site. The truck capacity plummeted (and costs have soared) as you need a special temporary permit to move in/out of the city.

- A major challenge for factories is getting raw materials and components needed to maintain production, while access to the ports has been sharply reduced and many supplies are stuck offshore on waiting vessels.

- Queues of bulkers have jumped since the start of lockdown in Shanghai. The congestion has expanded to nearby Ningbo-Zhoushan as ship-owners desperately divert ships to other ports in the country to avoid the trucker shortage and warehouse closures in Shanghai.

There were 477 bulk cargo ships

waiting off Shanghai as of 11th April 2022.

- Airfreight diverted from Shanghai is clogging up China’s other major airports, causing a shortage of pallets for exports.

- The reduced operations of factories, the shortage of drivers, limited operations in terminals, port congestion and the reduced number of available containers have created another huge chokepoint for global supply chains.

- Whilst Chinese officials have issued new guidelines to normalize industrial production and logistics flows in critical industries, the domino effect is inevitable.

"Lockdowns will likely impact China’s ability to export, which could eventually stoke inflation."

- European Union Chamber of Commerce in China

China raised its coal and gas output to record levels in March 2022. Coal production increased 15% on year, while natural gas rose 6.3%, according to the Statistics Bureau. The country aims to ensure energy security after coal shortages last year and to insulate itself from the surge in global prices triggered by the Russian war in Ukraine.

China’s Coal & Gas Boom May Help Ease The Energy Crisis

Lockdowns in China resulting in slower economic activity are likely to sharply cut the demand for oil in the country, potentially easing a supply crunch caused by sanctions on Russia, according to the International Energy Agency.

However, Chinese industry officials have expressed concern that they might not maintain record output for long and still may not prevent a return to electricity shortages in key industrial regions.

Weaker oil demand might ease supply crunch

- US ports are slowly recovering from last year’s congestion and delays. West Coast port congestion has started to ease as imports divert to the East. The US East Coast might become the next hot spot for severe congestion.

- It is predicted that as congestion in Chinese ports reduces post-Shanghai lockdown, destination ports around the world will be congested. When the wave of pent-up shipments reaches U.S. ports, it will reignite congestion on a scale similar to 2021, when nearly 100 container ships were parked in the ocean outside Los Angeles and Long Beach.

- US consumer demand continues to drive record import volumes as a much-heralded shift in spending from goods to services has failed to materialize. US retail sales in January increased 4.9% year over year, while retail inventories in December, the latest available data, rose 3.7% year over year, according to data provider Trading Economics.

- Potential labour disruption may soon hit US ports, as dockworkers have their enterprise agreements come to an end as of 1st July 2022. While contracts are still in discussion, historically, the period was marked by labour strikes. Some shippers are already pulling forward their holiday-season orders to avoid disruptions ahead of potentially contentious contract talks.

- On the westbound trans-Atlantic, port delays dragged schedule reliability down to a record low of 14.7% in February.

Chart: American Shipper based on data from eeSea

- The sanctions towards Russia are further impacting the equipment shortage. Containers that were on their way to Russia have been offloaded at transhipment ports in Europe. The lower import volumes from Asia over the Chinese New Year and the lockdown in Shanghai are adding to the container shortage.

- There is a shortage of trucks and drivers in North Europe. Several drivers, who are of Ukrainian nationality, went back home to defend their country.

- Many of the main container terminal hubs are suffering from terminal and landside congestion, attributed to the bunching of ultra-mega vessels and quaysides becoming overwhelmed with containers that have been previously omitted from schedules. The congestion at European seaports, especially at Hamburg, worsened after North Europe was hit by two storms in February.

- Vessels to Australia and New Zealand remain fully booked, especially all direct services. Sea freight rates to Australia remain on a high but stable level.

- Fuel surcharges are being applied for sea freight and all inland transport modes. Charges are reviewed on a fortnightly basis and are subject to further developments in oil prices.

- There is a shortage of wooden pallets in Europe. About 20 million pallets used to be exported from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine to Europe. Also, there is an acute shortage of nails, as steel comes from Russia; 70 to 80 nails are needed to make a single pallet. As a result, pallet prices have skyrocketed as the demand exceeds the supply.

What will the future of cargo shipping look like? Will things return to normal soon?

Here is what you can expect.

future outlook

2022

Freight rates aren’t expected to drop to pre-pandemic levels any time soon

Demand for goods will remain strong

Container shortages will continue

Port congestion will continue, especially in the USA

Ports will struggle to operate at full capacity – with threats of closures at short notice due to COVID-19

Unstable labour markets across Western economies, with union negotiations and port strikes

2023

We expect delivery of new vessels for 2023 to container shipping lines. Port congestion across the world will ease, and start to become manageable

Equipment will become more readily available

Freight rates will begin to stabilise, although will still remain high

Carriers who are not prepared to comply with IMO 2023 will need to reduce the level of vessels in service and thereby reduce capacity even more

2024

This is when we will start to see the market return to normality

New capacity will begin to enter the market

Carriers by this time will implement policies and procedures to balance their supply

Vessels will become more reliable, with the level of blank sailings reducing

Freight rates will further stabilise

Things Shippers Can Do Now to Prepare

Calculate your shipment using lead time and account for delays

Utilise smaller, less used ports where possible

Invest in one end-to-end solution with one provider to ensure a consistent partnership

Build a strong contractual relationship with your service provider

1

2

3

4

final tip

Engaging a professional to assess your current shipping process can save you time and money. This is particularly invaluable in 2022, when lockdowns, port congestion and capacity constraints across the globe are still at play.

With over 30 years' experience, International Cargo Express have highly trained staff that can cater to your business.

Engage the right Freight Forwarder

Container stevedoring monitoring report. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. 2021. Available at: https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Container stevedoring monitoring report 2020-21.pdf

Dierker, D., Greenberg, E., Saxon, S. and Tiruneh, T., 2022. Navigating the current disruption in containerized logistics. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/navigating-the-current-disruption-in-containerized-logistics

Global Liner Performance (GLP) report. Sea-Intelligence. 2021. Available at: https://www.sea-intelligence.com/press-room/97-schedule-reliability-drops-to-all-time-low-33-6-in-august-2021#:~:text=Although schedule reliability has hovered,has tracked global schedule reliability

Infrastructure.org.au. 2019. International Airfreight Indicator. Available at: https://infrastructure.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-International-Airfreight-Indicator-digital.pdf

Kay, G., 2022. The supply-chain crisis propelled the world's largest shipping company to its most profitable quarter in 117 years. Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/largest-shipping-company-maersk-most-profitable-quarter-supply-chain-crisis-2021-11

Knowler, G., 2021. Container shipping: Container shipping profits in 2021-2022 to hit $300 billion: Drewry. Joc.com. Available at: https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/container-shipping-profits-2021-2022-hit-300-billion-drewry_20211007.html

Koh, A. and Varley, K. 2022. China Port Congestion Leaves Everything From Grains to Metals Stranded. Bloomberg. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-11/477-bulk-ships-wait-off-east-china-s-ports-amid-virus-lockdowns

Leonard, M. and Leonard, M., 2020. Cargo rollovers rise as Maersk rolls more than 1 in 3 shipments in October. [online] Supply Chain Dive. Available at: https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/rolled-cargo-port-maersk-msc-coronavirus-singapore/589626/

Miller, G., 2022. East Coast ports about to get slammed by a lot more ships. FreightWaves. Available at: https://www.freightwaves.com/news/east-coast-ports-about-to-get-slammed-by-a-lot-more-ships

Placek, M., 2022. Global container freight index 2022. Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1250636/global-container-freight-index/

Siqi, J., 2022. ‘Serious disruption’: world’s largest container port hit by Covid surge. South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3172932/shanghai-port-operations-hit-citys-covid-19-outbreak

Wackett, M., 2022. Carriers forced to juggle schedules as congestion returns to North Europe. The Loadstar. The Loadstar. Available at: https://theloadstar.com/carriers-forced-to-juggle-schedules-as-congestion-returns-to-north-europe/#:~:text=Elsewhere, many of the main,have been omitted from schedules.

Xu, M. and Patton, D., 2022. China's daily coal output in March hits record high. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinas-daily-coal-output-march-hits-record-high-2022-04-18/

References